Every so often, you will see an article or a post on the role of philosophy in software testing. In 2023, for example, Joël Doat wrote Testing language models with the philosophy of Wittgenstein. This is an area that fascinates me, as it relates to the role of thinking in software development and testing.

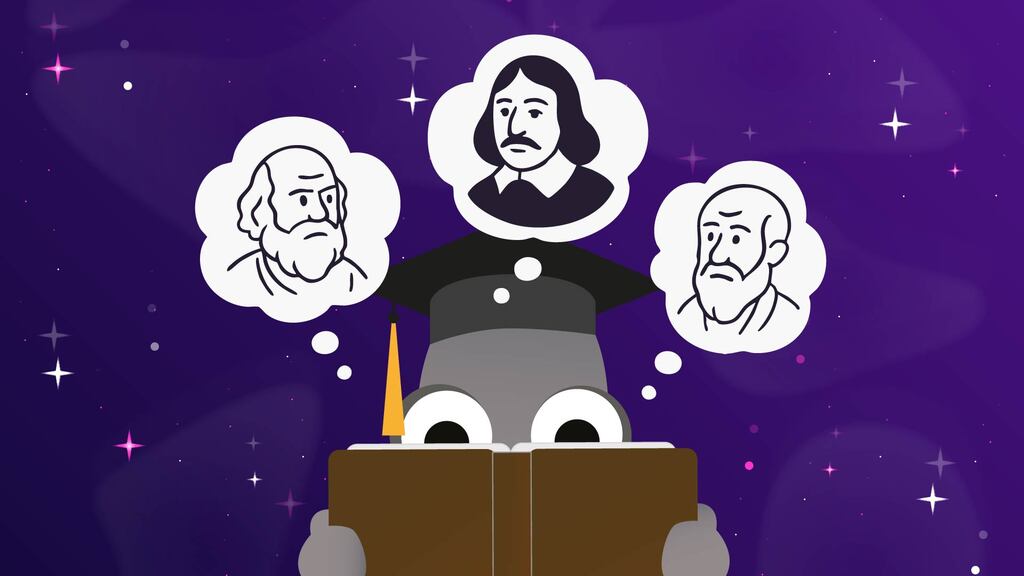

In this article, we embark on an intriguing journey, one that might seem a little outside the usual remit for us folks in software testing. We will delve into the realm of philosophy, examining how the deep thinkers of history can offer us valuable lessons for the software testing craft.

Why should testers care about philosophy?

At the root of a software tester's work is thinking. We are thought workers, paid for our ability to think critically and robustly. It is not only about asking questions, identifying and challenging assumptions, exploring risks, and making sense of complex systems. It is also about understanding the underlying principles that drive these processes. It is about doing so in a way that helps us build our understanding of the software under test. We are problem solvers and investigators, often critical of the software we work with, but from a constructive and supportive perspective.

So, when you consider all that, philosophers are, at their very core, thought workers too. They are deep and often very critical thinkers, who dive into the nature of reality, knowledge, ethics, and logic. It is clearer than ever to me that we testers share a lot of qualities with them. So, understanding how they think, and what they think about, makes sense to me. It helps me to understand how and why I’m thinking the way I am.

Philosophers look to understand the world by logically and deeply questioning, analysing, and reasoning through everything around them. The ways in which they think allow them to unpack complex ideas, identify flaws in arguments, and build frameworks for their understanding. Does that not sound quite a bit like what a good tester does every single day? Philosophers might not debug code, analyse requirements or acceptance criteria, and most don't write test automation. But their intellectual tools are surprisingly transferable to our goals of creating quality software.

This article will explore the wisdom of three widely known philosophers in the Western tradition. I hope to shed light on how their approaches can sharpen our testing mindsets and add significant value to our work.

Socrates: The questioner

It is hard to think of the great philosophers of the Western tradition without almost immediately thinking of ancient Greece. It was one of the most prolific breeding grounds of philosophers and one of the most influential figures from that time and place is Socrates.

Socrates understood the limitations of written texts and therefore chose not to write anything down. As a result, the knowledge we have of his ideas comes primarily from the writings of his students, especially Plato. Rather than staying in a classroom to discuss his thoughts with peers and students, he wandered the streets of Athens, engaging ‘ordinary’ Greek people in conversation. He challenged their most deeply held beliefs and assumptions through a method of persistent questioning. That method has come to be known as the Socratic method, and it can become heated and argumentative.

Areas of interest for Socrates were ethics, epistemology (the study of how we know what we know), and, in some cases, rigorous self-examination. He believed that wisdom lay in being aware of what you did not know: what we might call today the "unknown unknown." He believed that through rigorous questioning and debate, we can uncover deep personal truths and expose contradictions in logic and belief.

What do we testers have in common with a chap who lived over two thousand years ago and whom we know mostly from what he chatted about informally? A massive amount, as it turns out. Socrates' relentless pursuit of truth through questioning is the very bedrock of effective testing. We are paid to question. We are paid to be sceptical of what we are told and what we see. We are paid not to simply accept that something works, but to understand why it works, and more importantly, why it might not.

Applying the questioning mindset to software testing

Socrates' thought processes in software testing mean embracing the Socratic method in our daily work.

It is about asking "Why?" repeatedly, not just of the code or features, but also of the requirements, design decisions, and even our own testing approaches. If a requirement states something should happen, ask, "Why should it happen that way? What if it does not? What assumptions are we making about the user here?"

When a bug is reported, do not accept the apparent cause as the solution. Examine the underlying context, conditions, environment, and inputs until we can identify the root cause.

Socrates challenges us to question the obvious, to look as far beneath the surface as necessary, and to poke at contradictions until clarity emerges. This type of questioning can help us uncover hidden bugs and risks, gain a deeper understanding of complex interactions, and strive for truly robust solutions.

Takeaways:

- Cultivate relentless curiosity. Always ask the questions "Why?" and "What if?"

- Challenge everything, including the requirements and your own testing biases. Do not just accept surface-level functionality without testing the assumptions that underlie it.

- Embrace not knowing. Identifying those areas of uncertainty or that lack clarity helps you focus your efforts.

René Descartes: The doubter

The 17th century brought us René Descartes, a French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist, often hailed as the ‘father of modern Western philosophy.’ His most famous pursuit involved the systematic practice of methodological doubt. I know, right? What a mouthful. Practising methodological doubt is systematically questioning all your beliefs to find which are actually true.

Descartes set out to doubt everything. He worked hard to strip away all his ‘uncertain beliefs’ until he found something he could be absolutely certain of. This led to his famous declaration, ‘Cogito, ergo sum,’ or, said in a way I can understand it, ‘I think, therefore I am.’ An interesting way to prove you exist, when you can simply look in a mirror!

His areas of interest were epistemology (which I defined above with relation to Socrates) and metaphysics (the nature of reality, existence, or, as Douglas Adams would put it, life, the universe and everything). He believed in breaking down complex problems into smaller, more manageable parts, a process known as decomposition.

Testers, too, are, to some extent, professional doubters. While Socrates questioned, Descartes provided a systematic framework for that doubt. As testers, we cannot do our job if we don’t approach the software with a certain amount of healthy scepticism. It is reasonable to assume that nothing works as expected until it has been proven to work. This methodical doubt encourages us to avoid confirmation bias and to actively seek out scenarios where the software might fail.

Applying the doubting mindset to software testing

Descartes' approach means adopting a structured application of doubt in our testing.

- When we are testing something new that we haven’t encountered before, our initial mindset is to wonder how and if it works. We can treat every line of code, every integration point, and every user interaction as something to suspect, until it has been thoroughly explored and tested.

- Descartes' principle of decomposition is invaluable in testing. A large, complex system is overwhelming to test as a whole, even though we still need to take a holistic view to understand context.

- Breaking a system, feature, or any large task down into smaller, self-contained units for testing allows for controlled and manageable testing. By testing these smaller parts first on their own and then in combination via integration testing, we build confidence from the ground up, much as Descartes built his certainties from his examination of his fundamental truths.

This type of approach helps us ensure thorough coverage and identify bugs in isolated environments.

Takeaways:

- Apply your doubt to the software, deliberately assuming nothing works until proven otherwise.

- Break down complex systems, tasks, and features into smaller, more manageable, and by definition, more testable parts.

- Prioritise isolated testing to pinpoint bugs precisely and build understanding from fundamental components.

Aristotle: The observer

Our final stop brings us full circle, back to ancient Greece, to Aristotle. Aristotle was a student of Plato, but developed into a renowned thinker in his own right. He was interested in empiricism (which theorises that sense perceptions precede and underlie all other ways of acquiring knowledge) and logic.

Aristotle had interests that spanned logic, ethics, politics, metaphysics, and the natural sciences. In a departure from Plato, Aristotle placed greater emphasis on his empirical observations of the world around him, learning through his sensory experiences, and applying logical reasoning to draw conclusions. He was very particular in his classification of ‘things’ and understood the cause-and-effect relationships between them.

Testers, at heart, are empirical observers and logicians. We spend our days observing how software behaves, gathering evidence, and using logical deduction to understand why things are working (or not working) in a particular way. Aristotle's methodical approach to observation and his foundational work in logic provide a fantastic framework for our testing activities.

Applying the observer mindset to software testing

Aristotle's thinking means being disciplined in how we observe, explore and test software. We need to pay close attention to every detail, no matter how small: every error message, log entry, and every subtle change in behaviour.

- When we identify a potential bug, we use logical deduction to trace its possible causes, forming hypotheses and theories. Then we design targeted tests to prove or disprove them.

- His principles of classification can also be useful. We tend to categorise bugs by type, severity, or even component. We group test data and apply techniques such as equivalence partitioning and boundary testing, also known as boundary value analysis, which are rooted in logical categorisation. This is to ensure we execute efficient and effective testing.

- Understanding cause and effect relationships is crucial for effective bug reporting and ensuring that our fixes genuinely solve the problem and do not cause new problems.

Aristotle reminds us to trust our eyes, to trust our data, and to apply sound reasoning to every problem we encounter.

Takeaways:

- Be a meticulous observer. Trust empirical evidence and what the software actually does, not just what it is supposed to do.

- Apply rigorous logical reasoning to understand system behaviour and help pinpoint the root causes of bugs.

- Use classification and categorisation to organise your testing efforts, test data, and bug reports for greater clarity and efficiency.

To sum up

Philosophy might seem completely unrelated to sprints, requirement refinements, Three Amigos sessions and bug backlogs. In reality, the intellectual heritage it left us relates directly to the craft of software testing. We should embrace the questioning that Socrates applied to everyone and everything, the disciplined doubt that Descartes introduced, and Aristotle's practice of observation. We can then expand our testing mindsets, look to uncover more elusive bugs, and ultimately contribute to building even higher-quality software.

It is all about thinking about our thinking and then bringing that deeper level of thought to our daily pursuits, making our testing truly an intellectual endeavour. After all, we need to live up to our title as thought workers, don’t we? Or do we? Maybe that’s another philosophical discussion for another day. I think, therefore I test!

What do YOU think?

Got comments or thoughts? Share them in the comments box below. If you like, use the ideas below as starting points for reflection and discussion.

- Have you seen or thought of any other examples of the relationship between philosophy and software testing?

- What are the ways in which you think more deeply about testing, or even thinking about testing?

- What are your thoughts on thinking about the thinking we do?

For more information

- Testing language models with the philosophy of Wittgenstein, Joël Doat

- Metaphysics, Wikipedia

- Aristotle’s empiricism, Bryn Mawr Classical Review

- Life, the universe and everything, Douglas Adams

- Testing Ask Me Anything - Critical Thinking, Fiona Charles

- I think, therefore I test: the importance of thinking for testers, Ady Stokes