What prompted me to write this article: the app pane that goes "poof"

I am a writer and editor, and for many years, I tested software as a career. I use all kinds of software in my daily life.

And I am autistic. Do I have something to say about application usability for autistic people, and how software testers can help improve it? You bet.

Let me give you an example. One of my mobile applications provides a multilingual display, with commentary, of a text that is dear to the hearts of millions of people. It can display up to four panes of text or commentary at a time. It's a brilliant idea.

For the most part, it works swimmingly, until I start scrolling through and I accidentally hit the screen ever so lightly with my pinky finger. This happens a lot. POOF! Without warning or confirmation, a pane disappears, usually one of the panes I use most heavily. I then have to go digging through a menu to get the pane to reappear. And there's no online help to guide me as to how to disable the unwanted touchscreen behavior permanently.

Why does app behavior with regard to touchscreen input matter to us autistics (or, for that matter, people with conditions like essential tremor or Parkinson's)? Read on to find out more and learn about design recommendations to help autistic people use applications and websites.

What I will and won't write about here

Many applications and websites aim to help autistic people (usually children) navigate life in a world where people who aren't autistic are the majority. But, we autistic adults mainly use applications intended for the general public. Banking apps, eBook readers, YouTube and other video streaming providers, and so on. I'm more concerned with making THOSE apps more usable for autistic adults.

Also, the efforts to bring helpful applications to autistic children are admirable. But we autistic adults often get left out of consideration. So I won't be writing about design principles for autistic kids. If you'd like to see an article on that topic, consider submitting a proposal to MoT!

And a disclaimer: I am only one autistic person, and I would not dream of implying that what works and doesn't work for me is the same for all autistic folks. Read on and see what makes sense for you, and what doesn't.

Some things you might not know about autistic people, even if you are autistic

Is there such a state of being as "autism"? I believe so. Note that I used the phrase "state of being" instead of "condition" or "disease." That's because the medical model of autism pathologizes us autists without recognizing some of the actual advantages of being autistic. We are not sick people to be coddled, marginalized, or "cured."

I won't provide a definition of autism here. As they used to say on the X-Files, the information is out there. I define autism as a broad spectrum of idiosyncrasies that I share with many people.

So what are those idiosyncrasies? I hope some of these will surprise you! I cannot cover every single manifestation of autism in this brief article, so please do not interpret any omission as intentional on my part.

Autistic inertia: half of a task at a time, please

Shortly after I was diagnosed with autism in 2019, I started to hear autistic people talk about autistic inertia, sometimes called monotropism.

What do those fancy terms mean? Long story short, many autistic people have a hard time getting started on tasks (or simply getting off the couch), and many have trouble stopping a task once they start. This is classic autistic inertia.

To understand this phenomenon, think of our cognitive processing systems as similar to a water circulation system. The system of someone who is not autistic might feature several broad channels that gradually branch out into smaller ones. The autistic system, in contrast, doesn't have those big, broad superhighways. It feels like many small passageways instead. And so when a flood of input comes in, like a lot of sensory information at once or an urgent directive from our executive function, our cognitive processing gets clogged up.

Overwhelm from a lot of input all at once can lead to what presents as complete inactivity (in fact, we are massively overthinking). It can cause involuntary autistic meltdowns or shutdowns. This summary of how autistic meltdowns come about is helpful:

"When the brain becomes overwhelmed with too much information at once to process, anxiety during an activity (or in anticipation of an activity), or being subject to too many forms of information at once (e.g. multiple people talking, or talking while showing diagrams and images), sensory distress leads to dysregulation, which then gives way to a meltdown."

- All About Autistic Meltdowns: A Guide for Allies, Reframing Autism

Autistic inertia causes me difficulty in these areas:

- Engaging in a continuous stream of activity nearly all day long, the way non-autistic people can do

- Getting on with the next task if I am on a "rest break"

- Trying to accomplish a task that requires any level of focus when someone is talking to me. I will literally hold up my hand to indicate "quiet please" if I am trying to do something on my phone and someone starts talking to me

- A lot of sensory input at once, particularly loud sounds or a lot of different sounds

If I had to point to the one manifestation of autism that wears me out the most, it's autistic inertia. Yes, this affects how I react to user interfaces. But there are ways to mitigate that.

Sensory sensitivity: quiet please

On its own, even without the factor of autistic inertia, intense sensory input can literally be painful for us in ways that don't affect non-autistic people.

Sensory input that drains me:

- Loud or fast-paced talking, especially indoors

- Screechy phone microphones

- Loud or high-pitched mechanical or motor noises

- Overhead lighting

- Small physical spaces, especially if crowded

- Scratchy fabrics next to my skin

Physical coordination and awareness of your body in your environment

Are you kind of clumsy? I was clumsy when I was younger. It seemed SO HARD to learn how to do physical tasks (especially in the realm of physical exercise or sports) while I saw other kids mastering them with apparent ease.

You might often hit your head on low tree branches near a sidewalk, or knock into things like walls and doors. That has to do with proprioception, or how we perceive and are aware of our physical bodies in a space. Many autistics have legs and arms that always bear spots of green and yellow from bruises when they banged their shin on the edge of a table or had an unfortunate run-in with a car door.

I don't have as much trouble with klutziness as I used to. But one way I always remember being affected, essential tremor. I shake ever so slightly, and that shakiness has become more pronounced with age, especially in my hands. When entering a code on a smart lock, I often have to brace my hand against the edge of the door to avoid a series of errors in the entry. And my fingers tend to fly off and do "weird" things, and this is nowhere more visible today than in the use of a touchscreen. Touchscreens have reduced me to tears more frequently than any other interface type.

Words: fast, slow, or not at all

Reading superpowers and obstacles

Some of us seem to acquire the ability to read out of the blue. We aren't taught to read it just happens. Often, well before we begin kindergarten or preschool. This idiosyncrasy is called hyperlexia. And not only do we read, we read FAST, at least the language we learn first. What's more, we often can't help ourselves. We find ourselves automatically scanning words on a page or screen, even if we don't want to. Imagine what happens when an app or webpage presents us with a page that's jam-packed full of words. Usually, hyperlexia is a great asset, but sometimes it can get in the way.

Others of us are dyslexic, meaning we process written language very slowly, often confusing one word or letter for another. (This happens to me with alphabets that read right-to-left, like Arabic.) We skim text slowly, unlike hyperlexics. However, a page full of text will stop both hyperlexics and dyslexics in their tracks.

The spoken word is not for everybody: "text me please"

One consequence of hyperlexia is a strong preference for the written word. We would rather hear from you via text and respond in the same way. However, aiming a firehose of words at us, either spoken or written, can shut down communication entirely.

And some autistics speak seldom or not at all. These folks are often called "non-verbal," but this description is inaccurate because many are happy to use text-to-speech devices or communicate via text or sign language. A better descriptor is "non-speaking." This manifestation may be complete and lifelong, meaning that the person never learns to speak at all. Or it may become evident over time as a strong preference or occasional complete incapacity (such as during an autistic shutdown).

Lather, rinse, repeat, repeat, repeat: repetition and predictability

It's said, and much research shows, that autistic people like repetition and predictability. Some of us repeat words and simple behaviors ("stims") over and over. Throw a monkey wrench into our daily routines and we're done for, perhaps for the rest of the day (or week). Having a set daily routine of necessary and important tasks is, in fact, a great reducer of decision fatigue, not just for us but for non-autistic people too.

I am not always a fan of repetition. If someone repeats the same phrase to me over and over, for example, if I am learning a song lyric in a language other than my first language, I get irritated. But over the last few years, my daily schedule has become far more predictable than it used to be. Not surprisingly, I'm much less anxious.

Some researchers note that autistic people tend to gravitate towards and do well with computer technology because of its customary predictability, which is far greater than found in social interaction. So, when you have an enthusiastic user base like autistics, it makes sense to ensure that your applications are as appealing to them as is practical and possible.

Living in a society where not much comes naturally: coping with social deficits

We often don't form "the ties that bind," and we use apps instead

Many autistic adults do not have anything like a social network, and many don't even have family ties like spouses or children. Many of us struggle to form close, trusting relationships with others. Some of this has to do with the difficulty we have in processing multiple simultaneous streams of input and information, like social interaction, where both verbal and nonverbal signals must be heeded. (Monotropism strikes again!)

So, how do we navigate an increasingly complex, fast-paced world, especially since many of us move and work at a slower pace than average? Why, the Internet, of course! Many of us were early adopters of Internet technology, and we continue to rely on virtual connections with people and with information to buy what we need and chat with fellow nerds. And that's even when user interfaces don't exactly serve us well.

We don't respond "normally" to manipulation and social pressure

I marvel at how unthinking conformity comes so naturally to many people. They just "go along to get along" without adverse consequences (or so it appears).

In contrast, many autistics, myself included, teeter-totter between trying too hard to please people who don't like us and rebuffing social contact altogether after many bad experiences. As children and young adults, we're especially susceptible to being manipulated and controlled by untrustworthy people. Many autistics are great at learning to recognize patterns, however, and so some of us recognize patterns of untrustworthy behavior that we've seen before. We may even grow to be better at recognizing manipulative behavior than our non-autistic peers!

What does this have to do with app design? We can become allergic to apps that seem to prioritize the needs of the organization over our needs as users, especially if we are paying customers.

- If an app frequently forces me to jump through hoops in ways that don't serve me at all, I will eventually abandon it.

- For example, one of my current banking apps makes me click through at least two marketing-oriented pop-ups EVERY TIME I log in. If there's a way to disable this behavior, I'm unaware of it, nor do I have the time or energy to dig through the online help to find out. Eventually, I am likely to close this account, thanks in part to "features" like these in the app.

- Remember that autistic inertia in itself means that we experience greater cognitive load from normal day-to-day tasks than non-autistic people. Those needless button clicks, little by little, over time, add up to a lot.

How inclusive design makes technology friendlier for everyone, including autistics

Until last week, I was hemming and hawing over the draft of this article, trying to define "accessibility" and "usability," and mulling the implications of both attributes for making apps friendlier to autistics. All that was coming out was an unhelpful word salad.

Then my MoT colleague Ady Stokes pointed me to some pioneering work by Microsoft on a philosophy called inclusive design. I finally took a look at it, and I'm grateful I did so, for many reasons. (Microsoft did not coin the phrase "inclusive design," but their design and research communities are developing fruitful concrete methodologies for practitioners, including software development teams.)

What is inclusive design?

The Nielsen Norman Group has been doing pioneering work in usability and accessibility for decades. According to Google UX researcher Alita Kendrick in a post on the Nielsen Norman Group's website:

Inclusive design describes methodologies to create products that understand and enable people of all backgrounds and abilities. Inclusive design may address accessibility, age, culture, economic situation, education, gender, geographic location, language, and race…

At its core, inclusive design is about empathizing with users and adapting interfaces to address the various needs of those users. Inclusive design generates inclusive-design patterns.

How is this different from the time-honored concepts of accessibility and usability? It begins with the premise that if a design is not accessible or usable by some people, it's not accessible or usable, full stop. With this premise, we leave behind the mental bucketing that can come up when, say, someone says, "This meeting app needs to be accessible to people who do not speak." And so measures are taken to make the app accessible to people who cannot speak and who happen to use X assistive technology instead of speech. But those measures do not account for others who strongly prefer not to speak but who do not use X technology.

Why should we look to inclusive design principles for help with designing autism-friendly applications?

In contrast, as one Microsoft publication puts it, inclusive design may solve a problem for one specific group of people, but a good solution also brings benefits to many others.

- For example, high-contrast screens and adequate contrast between background and text are standard accessibility measures to aid those with visual disabilities. But those measures are also much appreciated by people who have to read a screen with a bright sun overhead.

- In the usability realm, outside the WCAG standards, adequate "negative" space on a page that contains brief and thoughtful text is a great boon for those who have trouble focusing. But people who aren't autistic or ADHD are increasingly interrupted and pulled off task too. So, a minimalist design with concise text means that they are also more likely to understand what the site is trying to convey.

Autism manifests in all kinds of ways and in many different degrees. For example, I am very limited socially, but I've never had trouble understanding metaphor, unlike many of my fellow autists. So, autism is a great example of a condition that is best met with a holistic philosophy like inclusive design. If you try to respond to the many barriers to accessibility and usability we experience with individual, concrete measures, you'll never have time to design or code anything else!

Research shows, over and over, that improving accessibility and usability for a specific group of people often means improvements for many others as well. Unsurprisingly, this holds true when we consider autistics in our application design.

So what do we need to do to make sites and apps easier to use for autistic people and their non-autistic friends? Read on!

Recommendations for autism–aware application design from researchers and from autistic people themselves

What researchers say: practising inclusive design pays off

Thirty years ago, I probably would never have received an autism diagnosis. The only difference between the years 2000 and 2019 (the year I was first diagnosed): tons of repeatable, solid research and clinical practice by and for women with autism.

Thankfully, usability researchers have followed suit in terms of interest in autistic people. Over the last 25 years or so, there's been a lot of research into what makes an interface usable by, and accessible to, autistic people, both young and old.

Specific user interface recommendations for autistic people

Some researchers have done surveys of the available studies on usability for autistics. They've evaluated them, excluding some that weren't helpful for various reasons. Then they've summarized the included studies and have created easily readable tabulations of all the accessibility and usability recommendations made.

Among these surveys, one of the best I came across is Toward Web Accessibility Guidelines of Interaction and Interface Design for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Below, you'll find excerpts from the recommendations they make, based on their far-ranging survey of existing research at the time. The entire set of recommendations is available in the article itself.

- Visual and textual vocabulary: Use simple visual and textual language, avoid jargon, spelling errors, metaphors, abbreviations and acronyms, and use terms, expressions, names and symbols familiar to users’ context.

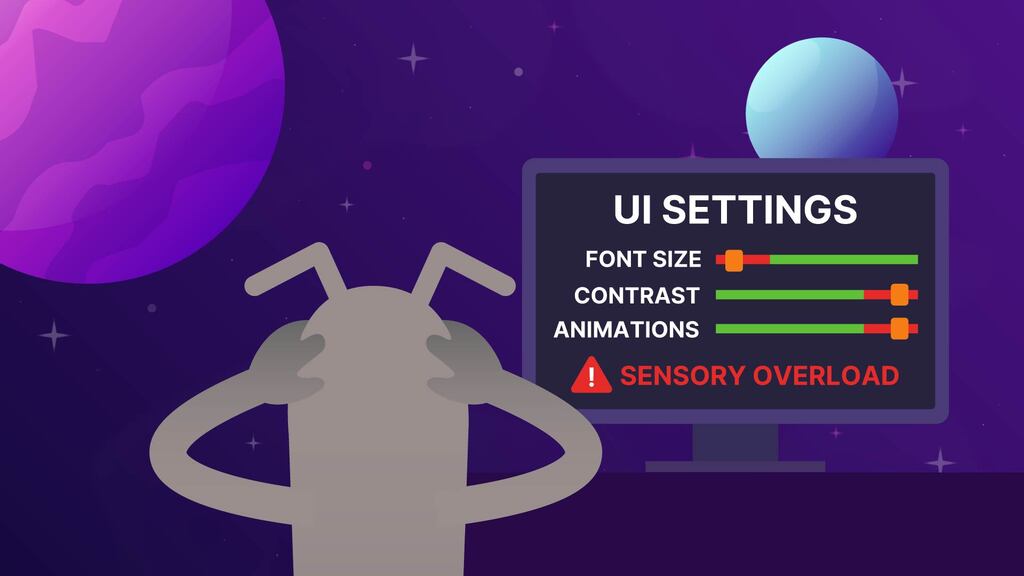

- Customization: Allow color, text size and font customization by the end user.

- Engagement: Avoid using elements that distract or interfere with focus and attention. In case you must use such elements, provide options to suppress them on screen.

- Redundant representation: The website or application must not rely only on text to present content. Provide alternative representations through images, audio, or video, and ensure that they are close in proximity to the corresponding text.

- Multimedia: Provide information in multiple representations, such as text, video, audio, and images, for better content and vocabulary understanding, also helping users focus on the content.

- Feedback: Provide feedback that confirms correct actions or alerts the user about potential mistakes. Use audio, text, and images to represent the message, avoiding icons with emotions or facial expressions.

- Intuitive navigation and interaction: Elements and interactions that appear similar must produce similar, consistent, and predictable results.

- Navigability: Avoid automatic page redirects or expiration time for tasks. The user should control navigation and the time needed to perform a task.

- System status: In interactive lessons and educational activities, allow up to five attempts before showing the correct answer.

- Touch screens: Touch screen interactions should have the appropriate sensitivity. The interface should prevent errors in selection and prevent unexpected consequences of accidental touch, in interface elements.

Research into inclusive design for "everyone" often goes double for autistics

As I gathered material for this article, my web searches usually included the word "autistic." Unsurprisingly, I found research done solely with regard to autistic people. But then I asked MoT for guidance, and Ady made his recommendations on inclusive design.

The article Respecting Focus by Microsoft's Inclusive Design team deals with the effects of alerts on our focus and ability to perform tasks, and how to design alerts so that there are "just enough" of them at the right times. The article addresses this concern in a way that makes sense for both neurodivergent and neurotypical people alike.

"When technology communicates and behaves well, it enables you to do what you want to, on your terms.

When alerts appear at inopportune moments, even the most useful notifications can have detrimental results like anxiety, frustration, and reduced productivity.

Careful observation and empathetic conversations with individuals and groups are key to understanding how alerts work for and against them.

When designing any form of communication, determine how much attention it needs and when: Full attention, partial attention, little attention."

The design of the article by itself is a great example of the use of negative space, images, and brief, clear text. Look at the ample white space and the style of the images, and notice how you feel. (I feel calmer while looking at it, although you may not!)

From what I have seen, I can't praise the work of Microsoft's Inclusive Design team too highly. If you're interested in solid application design for neurodivergent people, including autistics, please take a look.

What autistic people themselves say about helpful and unhelpful application design

Autistic people who work in usability

Are there any prominent autistic folks who have spoken about what works for autistics in terms of interface design? Why, yes! Jamie Knight is an autistic man resident in the UK who consults on usable design for everyone, especially neurodivergent people. He was interviewed about autism and technology back in 2009. Among his observations:

- For Jamie, sensory and processing issues are the most significant manifestations of autism.

- When he gets overwhelmed or stressed, he can lose the ability to speak. He notes that once he was unable to speak for seven whole months, and during that time, he used the large view system in the Mac Quicksilver App and the text function on his phone for messaging.

- Like many autistics, he's a computer tech enthusiast. "The web for people with autism is very, very empowering. It gives you a communication medium where many, if not the most complicated social norms, are not present."

- One of his favorite interfaces was the Coda IDE: "I find that the concept of a super simple one window development environment very appealing, little touches like remembering open tabs when switching between projects and even some of the visual simplicity make it something I enjoy working with."

- He frequently encounters bad UX on rail booking systems: "The interfaces are busy, often erratic, and they will display times which are not actually available. Travel is one of the things I find most stressful, and part of why I keep my travelling to the simplest routes (get on train, get off train… arrive), the websites further compound the problem."

Autistic users of technology

Autistics like me have our favorite online hangouts, and one of mine is Ask Metafilter, where community members can pose just about any question under the sun.

I know the community to be chock-full of fellow neurodiverse folk. We call ourselves "MeFites."

And so I asked my fellow MeFites:

"In your journeys through tech:

- Which apps, websites, gadgets would you call out for excellence (or simply good quality) because it seems like someone thought about usability for a broad range of people, including folks with sensory and cognitive quirks like us autists?

- Which tech have you had to abandon because it drains you of spoons, confuses you, angers you? And you had that reaction due to one of your autistic traits?

- Perhaps you remember specific features common to many apps and gadgets more than you remember specific apps or gadgets. That's the case for me. Naming those features are valid answers to this question!"

You can read the responses for yourself. I see some common themes:

Distrust of apparent intent to distract and manipulate, not to serve the end user. Ever hear the phrase "pull focus?" That's the effect of these design elements, and it is likely intentional. Distracting users from the task they intended to do places an especially heavy load on autistic people. Some examples:

- Autoplaying video and audio

- Popups, popups, popups, especially those with tiny or obscure X buttons to close them

- Interstitial links that appear while you are scrolling through an article with the intention of reading it

- Autoscrolling banners

- Animations that strobe, which can actually cause seizures in some people

- Extraneous information that usually is about marketing and sales ("46 people bought this item last week!")

- One MeFite wrote: “My attention is a limited resource. If your website/system has decided to abuse this limited resource for advertising purposes, I will have to stop using it.”

Preference for text-only sites and displays over those that use multimedia. This goes against some research recommendations that autistic users understand site content better when images accompany text. The apparent contradiction is probably due to the fact that multimedia is often used poorly, putting the needs of the end user at the bottom of the priority list.

- Rapidly moving or flashing design elements triggered vertigo for several MeFits.

- One MeFite wrote in response to others' comments: “Echoing the hate of anything that pops up, moves, makes noise, plays video, etc, without me starting it, and the love for MetaFilter's simple text-based design.”

Preference for user control of most design elements, including the presence of images, color, text size, and more. Among the many comments on this aspect of UX: “I REALLY like apps where I can customize the colours of the theme, just because it gives me a deep sense of joy to be able to play with colours and helps me engage with that app.”

Preference for consistency and predictability. Sites that frequently change their navigation patterns or site structure, for example, are disliked. One MeFite wrote: “Keep the same look and functionality for years instead of constantly moving things around.”

Dislike of built-in gamification. Again, this goes against some research that found better engagement among autistic people when an interface includes games.

- However, emphasizing the importance of user control, the MeFite used the phrase "forced gamification," and especially disliked a social competitive element in the games that the UI imposed on the user.

- The same MeFite went on to say that “gamification can help a lot, for example, I'm enjoying using Finch, a self-care to-do list app.”

A notably higher level of emotion with regard to sites and apps that are not designed well. You'll see a lot of anger and frustration in the comments.

- Remember what I wrote above about how autistics rely heavily on tech to navigate their worlds?

- When that very same tech costs us hours of time and tons of energy to recover from unpredictable navigation behavior, for example, it really sends the spoons flying out of the drawer. Unfamiliar with "spoon theory" with regard to living with a disability? Read about the spoon theory here!

- Poor design is costly in terms of time and energy for non-autistic people as well. But they're far more capable of recovering quickly.

To sum up

What can you do to start to influence app design that works for autistic people?

- Advocate and educate your team on good inclusive design principles. Do a presentation!

- Point out to your team and stakeholders that designing apps to make them more usable for autistic and other neurodivergent people will likely make them more usable for everyone. That can mean a better bottom line in terms of profit for the business. If you work in a regulated industry or if your product is likely to have a large autistic user base, you can make the argument with greater success.

- Do you use an app or a website whose usability is made worse by any of the problems discussed above? File a bug or problem report in the app store. Post on social media and tag the company. If the problem is bad enough, consider finding a replacement for the app and let the publishers know why you're cancelling your subscription.

- If you're not autistic, spend time listening to autistic people. You can find some good resources below in the For more information section. Join user communities and subReddits where autistic people hang out, but be aware that you are there to LISTEN and LEARN, not to make unsolicited suggestions.

What do YOU think?

Got comments or thoughts? Share them in the comments box below. If you like, use the ideas below as starting points for reflection and discussion.

Questions to discuss

- Are you autistic? If so, did this article leave anything out that you think is worth mentioning? If you are not autistic, please let autistic folks do the commenting and reflect on what they share.

- Have you ever had to test software when you weren't confident that the design would serve the user base well? What did you do, if anything? How did it work out?

- Do you or a loved one have a disability or other condition that makes software harder to use than it should be? What, if anything, have you done to try to change things?

- How can we best combat bad design decisions when they are coming from people with clout in your organization?

- Is there any power in refusing to use software that doesn't serve you well when so many people (and organizations) simply "put up and shut up"?

Actions to take

- Subscribe to one of the podcasts listed below and have a listen.

- Next time you encounter a website or app that is likely to cause problems for some autistic people, file an issue report and point them to one of the research studies mentioned in this article.

- If a website or app appears to be designed in a way that will help autistic people, give the organisation a shoutout on social media.

For more information

- Inclusive Design at Microsoft

- Toward Web Accessibility Guidelines of Interaction and Interface Design for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Talita Cristina Pagani Britto and Ednaldo Brigante Pizzolato, 2016

- Accessible and Usable Websites and Mobile Applications for People with Autism Spectrum Disorders: a Comparative Study, Antonina Dattolo, Flaminia L. Luccio, 2017

- Monotropism.org, an information hub created and maintained by Fergus Murray, one of the two people who coined the term and did the initial research. His first research partner was his late mum, Dr. Dinah Murray, and the site houses an archive of her research as well.

- Meet My Autistic Brain, a light-hearted podcast featuring reflections on aspects of living with autism by a woman diagnosed in middle age

- Echoes Without Origin, a YouTube channel from a late-diagnosed autistic woman with ADHD, aphantasia, and a memory disorder called SDAM

- Making jobs easier for neurodiversity: Manual of Me

- TestBash 2023 discussion: Accessibility, Diversity, and Inclusion