Activity (50)

Article (335)

Ask Me Anything (55)

Chat (72)

Club Topic (28)

Course (37)

Discussion Panel (44)

Feature Spotlight (58)

Term (608)

Into The MoTaverse Episode (12)

Certification (83)

Collection (251)

Masterclass (92)

Meme (234)

Memory (3480)

Newsletter Issue (230)

News (329)

Satellite (2891)

Solution (81)

Talk (226)

MoTaCon Session (872)

Testing Planet Session (105)

Insight (210)

TWiQ Episode (295)

A quality police dynamic can occur when teams become divided, and Quality Engineers are positioned, explicitly or implicitly, as the people who “approve” work. In this situation, they can become de facto gatekeepers rather than collaborators, which may create an “us vs them” dynamic in teams, lead to defensive behaviour around incidents and bugs, and reduce psychological safety.

Impact

Developers and engineers may disengage from quality ownership.

Quality Engineers may be blamed for missed issues.

Collaboration may decrease rather than increase.

Root cause This may happen when shared ownership is talked about in teams, but accountability is not truly shared. It can be noticeable in teams where authority remains centralised while responsibility is supposedly distributed.

A toast message (or often simply referred to as "toast") is a small, non-modal notification that pops up briefly on a screen to provide feedback about an operation.Key characteristics:

Non-intrusive: It appears over the UI but does not block the user from interacting with the rest of the application.

Transient: It disappears automatically after a few seconds without requiring the user to dismiss it, and goes away quickly.

Informational: Typically used for low-priority updates, such as "Message Sent," "Settings Saved," or "Item Added to Cart."

Traditional software testing is the process of evaluating a software application through test scripts to ensure it meets specified requirements and is free of bugs.In a traditional (often Waterfall) environment, testing is typically a distinct phase that occurs after the code has been fully developed but before the product is released to the user.Key characteristics

Sequential timing: It usually follows a "test-last" approach, occurring at the end of the development lifecycle.

Verification & validation: It confirms the software does what it was designed to do (Verification) and ensures it fulfills the user's actual needs (Validation).

Documentation-heavy: Relies on formal and detailed test plans, test cases, and requirement traceability matrices, without much room for flexibility.

Goal-Oriented: The primary objective is to identify bugs, errors, or gaps in the software to ensure quality and reliability.

Pros and consThe Pros

Stability and clarity: Since testing starts after the design phase, the "goalposts" rarely move. Testers know exactly what to look for based on fixed documentation, which can be good for heavily regulated industries where requirements can be very explicit, specific and detailed.

Structured control: It’s easy to track progress and milestones. You know exactly when the testing phase begins and ends.

Discipline: The heavy emphasis on documentation (test plans, scripts, and logs) creates a highly traceable audit trail, again a big plus in regulated industries.

Reduced complexity: Because the software is "finished" before testing starts, there’s no need to worry about the code changing while you're trying to find bugs.

The Cons

Risk and rigidity: Late Bug Discovery: Finding a fundamental flaw at the very end of the cycle is expensive and time-consuming to fix, which means that testing is often perceived as a bottleneck.

High risk of delays: If testing reveals a major issue, the entire release date is pushed back, as there is no "buffer" time. This can lead to bugs being ignored or swept under the rug.

Lack of Flexibility: It’s very difficult to pivot. If a user's needs change halfway through development, traditional testing usually can't account for it until the next major version. The result of this rigidity is additional costs, in terms of time and money.

The "Wall" effect: There is often a disconnect between developers and testers, leading to a "throw it over the wall" mentality rather than collaboration. Isolated teams communicate less effectively, which can cause misunderstandings and rivalries.

An Individual Contributor (IC) is a role where your impact mainly comes from doing the work yourself, not from managing other people. A simple way to think about it:An IC is like a senior person on the team who still builds things. They may review work, help others, or influence decisions, but they are not responsible for running the team.In Quality Engineering, an IC might:

Test or investigate issues

Improve tooling or checks

Review work and point out risks

They create impact mostly through their own work and judgment, not through people management.

Test pollution happens when one test leaves behind data or a system state that affects another test. The failure appears unrelated, but the root cause is shared context leaking between tests.This usually shows up when shared data is not cleaned up, system state is reused unintentionally, or resources remain locked or modified after a test finishes. As test suites grow, these hidden dependencies create failures that are hard to reproduce and even harder to trust.For example, a user registration test creates abc@xyz.com but doesn’t delete it. Later, another test tries to register the same email and fails with “email already exists.” The second test looks broken, but the real issue is that the first test polluted the system. The failure depends on execution order, which makes it flaky and misleading.The core problem is not the assertion, it’s isolation. Reliable tests must assume they run alone. That often means rolling back test transactions, generating unique test data, or running tests in disposable environments such as containers that are destroyed after each run.One way teams uncover test pollution is by running tests in random order or executing individual tests in isolation. If results change based on order, hidden dependencies are already present.

Coverage illusion is the false sense of confidence that comes from having high test coverage numbers without actually testing what matters. It happens when metrics suggest that a system is well tested, but important behaviours, risks, or failure scenarios remain unexamined.This illusion often appears when tests focus on executing lines of code rather than validating outcomes. For example, a test may pass through a piece of logic without checking whether the result is correct, or it may avoid meaningful edge cases while still increasing coverage percentages.Coverage illusion is risky because it shifts attention from understanding behaviour to chasing numbers. Teams may believe the system is safe to release because coverage looks good, even though critical paths, integrations, or assumptions have not been tested properly.Avoiding coverage illusion means treating coverage as a signal, not a goal. Good testing looks beyond what was executed and asks what was actually verified, what could go wrong, and what evidence exists that the system behaves as intended under real conditions.

State leakage happens when data, configuration, or system state from one action, test, or user session unintentionally affects another. Instead of starting from a clean and predictable state, behaviour is influenced by something left behind earlier.This often shows up in tests that pass when run alone but fail when run together. For example, a test might rely on data created by a previous test, a user session might remain active longer than expected, or a cached value might change the outcome of a later action. The system appears inconsistent, even though the logic itself has not changed.State leakage is risky because it hides real problems. Tests may pass for the wrong reasons, failures may be hard to reproduce, and bugs may only appear in certain orders or environments. This can lead to flaky tests and false confidence in system stability.Reducing state leakage involves being clear about setup and cleanup, isolating tests where possible, and validating assumptions about system state. When state is controlled and predictable, behaviour becomes easier to reason about and failures become easier to trust.

A silent failure is a situation where a system fails to behave as expected but does not surface any visible error, alert, or warning. From the outside, everything appears to be working, even though something important has gone wrong underneath.This can happen when errors are swallowed, logs are missing, validations are skipped, or failures are handled in a way that hides their impact. For example, a background job may stop processing data, an event may never be triggered, or a user action may be ignored, without anyone being notified.Silent failures are particularly risky because they create false confidence. Tests may pass, dashboards may look healthy, and users may not notice a problem immediately. The issue is often discovered much later, sometimes only after data is lost, trust is damaged, or downstream systems break.Identifying silent failures requires testers to look beyond visible outcomes. This includes checking side effects, data changes, system state, and assumptions about what should have happened. Good observability, clear expectations, and thoughtful test design help reduce the chance of silent failures going unnoticed.

TeamEx is basically the collective health, morale or "vibe" of how a team works together. Think of it as like DevEx (Developer Experience), but instead of just focusing on coders, it’s about the whole team. It’s the social and organisational scaffolding that makes working together feel human, reliable, and, dare I say, actually enjoyable.You know a team has good 'TeamEx' when you see:

Psychological Safety: Open communication means people aren't afraid to say "I don't know" or "I’ve made a mess of this."

Trust and Collaboration: No silos, no "us vs. them". Just people solving problems and listening to each other's ideas and suggestions without judgment.

Failures as Lessons: When something breaks, the first question isn't "Who did this?" but "What can we learn?"

Feedback as Routine: It’s not a scary annual event; it’s just part of the daily conversation.

TeamEx matters because it supports turning quality from a task into a habit. You can have the best test automation in the world, but if the team doesn't feel safe or empowered to speak up about a risk, that technical work is wasted.When TeamEx is high, testing throughout the SDLC and continuous improvement become part of the team's DNA rather than something tacked on at the end. It’s the difference between a team that’s constantly firefighting with short-term fixes and a team that consistently builds stuff that lasts.It’s not just about individual metrics or how fast one person can work. It’s about how quickly the group recovers from problems, how they make collective decisions, and whether everyone feels engaged, valued, seen and heard.

Defect Seeding is a testing technique where you deliberately add known bugs into the software to evaluate how effective our testing really is. Let's think of it as testing the test process itself.If testers or automated tests can catch these planted defects, it’s a good sign that the testing approach is working. If many of them go unnoticed, that’s a signal that coverage is weak or certain risk areas are being missed. This technique is also used to estimate how many real defects might still be hidden.For example, if testers find 15 out of 20 seeded defects, we might assume a similar detection rate for real bugs.However, this only works if the seeded defects behave like real ones, which isn’t always the case.Because it takes effort and careful planning, defect seeding is mostly used in research or controlled environments rather than day-to-day projects.

Cognitive complexity is a software quality metric that quantifies the mental effort required to understand code. The cognitive complexity meaning refers to how difficult it is for an engineer to read, comprehend and work with a piece of code.The cognitive complexity function encompasses several key elements. Cognitive complexity starts with a base score of zero and adds points for specific code patterns: decision points, nested level, flow interruption, recursion, and logical operators. The total score reflects how challenging the code is for a human to follow. For example, a simple if statement adds 1 point. That same if statement nested inside a loop adds 2 points (1 for the condition, +1 for nesting). A nested if with multiple logical operators could add 3-4 points.High cognitive complexity slows development, increases bugs and makes code harder to maintain.Cognitive complexity is one of the most overlooked barriers to developer productivity. When code becomes difficult to understand, it slows down every part of the development process: debugging takes longer, modifications are more likely to introduce bugs and onboarding new developers becomes a costly exercise in confusion. This also applies to testers working on test automation: debugging test failures takes longer, modifications are more likely to introduce complexity, duplication or code that does not represent the desired behaviour of the system under test and onboarding new people to work on the automated tests becomes a costly exercise.

The OpenAPI Specification (OAS, formerly Swagger Specification) defines a standard, language-agnostic description format for HTTP APIs, typically written in YAML or JSON. An OpenAPI file allows you to describe your entire API, so that users can understand the capabilities of the service without access to its source code, or through network traffic inspection. OpenAPI Specifications typically including available endpoints (/users), operations on each endpoint (GET /users, POST /users) and operation parameters (input and output for each operation).

Jira Issue Connect brings live, real-time Jira data directly into TestRail, eliminating tab-switching and stale fields.

Get hands-on fast. AI-assisted test creation, and CI-friendly execution.

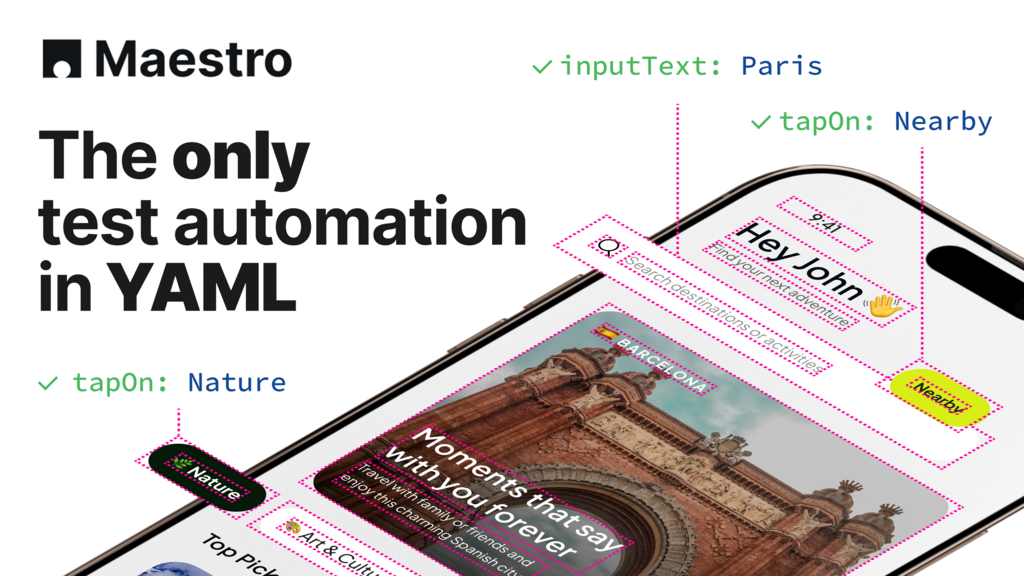

Create E2E tests visually. Get clear, readable YAML you can actually maintain.

With servers in >250 cities around the world, check your site for localization problems, broken GDPR banners, etc.