When I started out in testing, I thought the job was all about tools and bugs. If you could automate a flow or break a feature, you were doing your job.

Then came the uncomfortable part. I started to learn that testing wasn’t only about catching what’s wrong, but also about understanding why things work the way they do. Working with my mentor, Varun, didn’t feel like mentorship in the usual sense. There were no big lessons or checklists to follow. Just little nudges that made me stop, think, and question how I approached problems.

Looking back, what I learned from him wasn’t a list of tips or rules. It was a structure. A way to think about problems, systems, and people. A framework that still shapes how I approach product quality.

Here’s what that looked like over time.

1. Foundation: Thinking before doing

I used to jump straight into “how.” New task? Open the code editor, do it, run it.

Every time, Varun would ask me a question I couldn’t answer initially: “What are you solving here?” “Why are you solving that?” It annoyed me because it slowed me down. But those pauses changed many things.

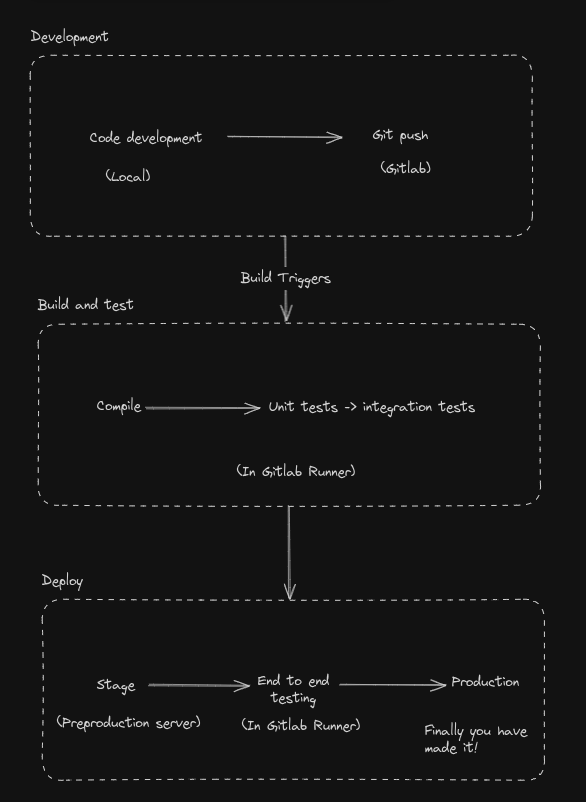

I started writing just to clarify my thoughts before touching anything. When words didn’t work, I drew. For example, I once sketched a quick flow of requests just to understand what was making it slow. Nothing fancy, just boxes and arrows: “this triggers that,” “user goes here.” Just to answer those questions.

It gave my testing a context. I stopped checking boxes and started connecting dots. Pausing like this helped me see where my work sat in the wider system, not just the task in front of me.

Takeaway: Don’t start with “how.” First, figure out “what’s the actual problem?” It saves hours later.

What this looked like in practice:

- Before you start any task, write or draw it on paper - even a rough sequence like Login → user clicks card → API call → expected result.

- Ask yourself what the impact of the work is on you and the user

Basically, this is to answer would doing this work adds to something in your skill and how that work will be helpful for that user - If you can’t map the problem in words, pause. You are not ready to execute yet.

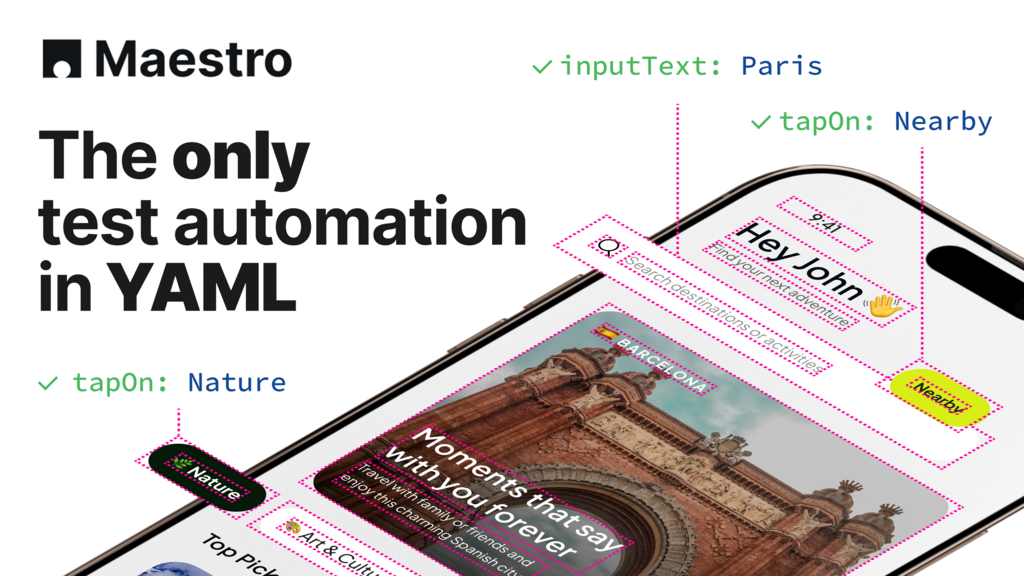

Like this was one I made once you understand how developers work:

2. Structure: Systems over symptoms

We once had a release where the same flow kept breaking: log in, search on a keyword, something weird happens, repeat.

Each developer put in their own fix for it, but the issue kept coming up anyway.

That’s when I heard from Varun: “Fix the reason, not the situation.”

And I realised we weren’t fixing the bug. We were fixing its effects. Once we looked at the setup and processes behind it, the “flaky” bugs disappeared.

Now I don’t stop at asking “Why did this break?” I also ask, “What allows it to keep breaking?” That question pushed me to look at the interactions between parts of the system, not just the failure itself.

Takeaway: The real test of learning is how well it continues without you.

What this looked like in practice:

- Map the full flow that the bug touches - the services, data, and dependencies involved.

- Compare what changed versus what didn’t change. Recurring issues often hide in the parts no one revisits.

- Identify the condition that makes the bug possible - the config, data shape, environment drift, or unclear assumption.

You would end up finding the real problem.

3. Sharing: Reiteration and growth

For a good while, I used to fix things quietly, without much comment to others, and then move on. Then Varun suggested: “Share your learnings to learn more.”

Sharing was a wild idea for me. I used to avoid it at any cost. But when I started sharing, people added their perspectives, and I learnt faster. This let me know that sharing isn’t simply about documentation, it’s how you multiply understanding.

Many of my better testing habits came from what others shared in return. And if that shift hadn’t happened, you wouldn’t be reading this. Talking openly about what I was learning helped me and the team better understand the system, because everyone brought different pieces of information.

Takeaway: Writing what you learn helps the team learn faster. Knowledge stuck in your head doesn’t scale.

What this looked like in practice:

- Share a quick TIL(Till I Learn - a one line summary) in your team chat - a one-line summary of something you figured out.

- Turn repeated explanations into a simple note that others can refer to later - write it once as an email or a small doc and share it with the team.

4. Refinement: Ownership and judgment

Once, a bug in code I had thought I tested thoroughly slipped into production. I had done my checks, but it still made it through.

I was ready to defend myself. “I tested it properly.” Instead, the question Varun asked was: “How do we make sure this doesn’t happen again?”

That question, answered repeatedly, changed how I viewed ownership. It’s not about defending what you did. It’s about improving how the system works.

Takeaway: If it’s your area, own it fully, even when it fails. That’s how better judgment forms.

What this looked like in practice:

- When something goes wrong, find what got missed from your end and what needs to be changed to improve it.

- Review your test flow whenever you miss a bug.

- Proactively flag bugs before someone asks.

- Treat every missed bug as data and not an accusation.

For example, a bug once slipped because I assumed users would always follow one path through the flow. Replaying my steps showed that I’d never tested the alternate entry point. When Varun asked, “How do we make sure this doesn’t happen again?”, it turned that small assumption into a shift in how I review flows and plan tests.

5. Continuity: Letting go and growing others

At some point, the focus shifted from learning to helping others figure things out. I stopped being the “new tester.” As new people joined the team, I found myself explaining and forwarding the ideas I had picked up from Varun.

I noticed that what worked for me wasn’t always obvious to others, especially the small habits like drawing flows or writing down discussions, or celebrating small wins. Sharing those made a bigger difference than explaining “how to test.” It helped people think about how things connected in the system, not just follow a list of test steps.

Working with Varun helped me understand how to work with people who challenge you instead of agreeing with you without reflection.

Takeaway: “You choose people you want to work with.” That’s one thing he said that stayed with me.

What this looked like in practice:

-

Share your reasoning with impact and not just conclusions.

For example, instead of saying “Do it this way” walk through why you chose that approach or what risk you were addressing. -

Celebrate small wins. They matter more than big milestones early on. (This was one of the hardest habits for me to build.)

This could be someone asking a good question, noticing a pattern or improving a test flow.

To wrap up

I still pause before jumping into “how.”

I still reframe issues as signals from the system.

There was no manual for it. Just constant, quiet pushes in a certain direction. That’s the thing about mentorship to me. It doesn’t hand you answers, it rewires how you think.

It took me time to understand that. It started by asking my mentor for answers (and getting annoyed when I didn’t get them). And I ended up learning how to find those answers myself.

What do YOU think?

Mentorship affects how we think long before we realise it. Got comments or thoughts? Share them in the comments box below. If you like, use the ideas below as starting points for reflection and discussion.

Questions to explore

- What habit or mindset did you pick up from someone quietly guiding you?

- When something breaks, do you fix the issue or the system around it?

- What repeated issue in your team might point to a system-level cause?

Try out

- Before starting anything this week, write one line: “What am I actually solving?”

- Draw one flow for a feature you work on, even if it’s messy.

- Share one learning with your team. Just one.

For more information

- When Your Mentor Moves On: Dealing with A Change In Ideal Leadership, Brian J. Noggle

- Do software testing professionals understand what is meant by systems thinking?, Mike Harris, Rosie Sherry, Rahul Parwal, Anders Wallin, Rachel Kibler, Peter Whitfield, Jane D'Cruze

- Learning To Learn - My Struggles And Successes!, Danny Dainton