Richard Adams

Senior Test Analyst

He / Him

I am Open to Teach, Speak, Podcasting, Write, Meet at MoTaCon 2026

Passionate about quality & testing. Creator of Threat Agents card game and regularly found chatting cyber security.

Achievements

Certificates

Awarded for:

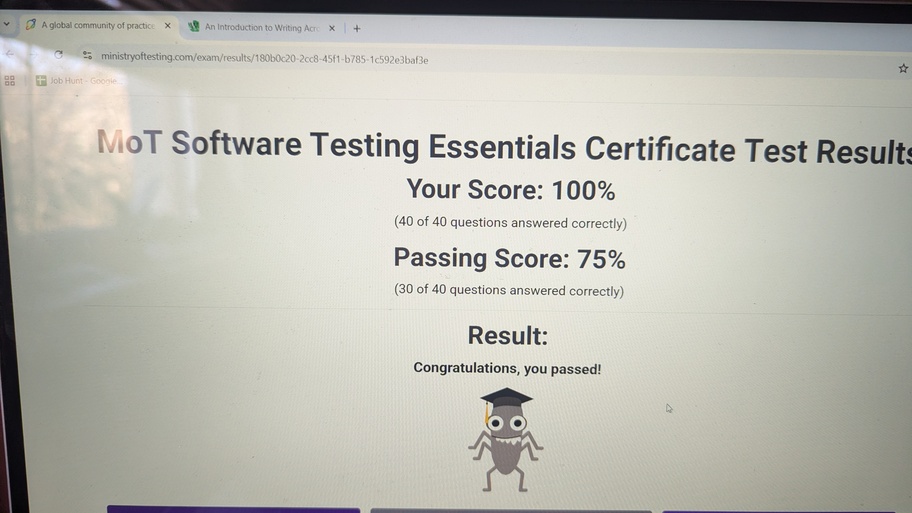

Passing the exam with a score of 100%

Awarded for:

Achieving one or more Community Stars in five or more unique months

Activity

earned:

Ask Me Anything about Security in Testing

earned:

Ask Me Anything about Security in Testing

earned:

This Week in Quality

earned:

Lesson 5 of Everyday security testing: A practical guide to getting started

earned:

Rewind to my first in person event

Contributions

With recent excitement about Chapters, it got me thinking of the first time I ever went to an in person testing event. I had only just switched back from development to test and wanted to engage wi...

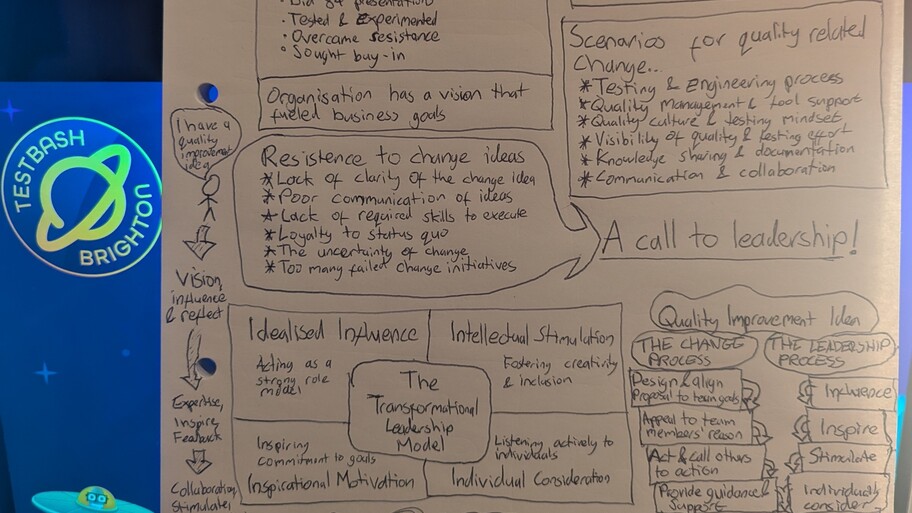

I was overdue doing some sketch-noting and decided to go with a talk I'd seen but was keen to see again. At MoTaCon 2025 Barry Ehigiator delivered a fantastic talk called "Beyond the titles: leadin...

An issue reported by a customer to the support team that requires involvement from the engineering team. This may be because the issue is a defect or require deeper diagnosis & analysis by engineers (developers or tester) to understand the behaviour that the customer is experiencing and advise them on steps to resolve their problem. Companies often have policies or Service Level Agreements (SLAs) that define how quickly engineering teams must respond to and resolve escalations from customers.

My first goal for 2026 was to get certified. I have taken my STEC exam, albeit with a couple of lessons to complete, and passed. Pretty darn delighted and my CV is already updated ready for some jo...

After a year that mixed highs and lows, ending with me looking for work, I have three key goals to help me come back stronger.

1. Getting certified: I've started STEC and signed up for SQEC plus...

Explore how testers are blending AI with human judgment to improve exploratory testing, sharpen risk thinking, and stay accountable for quality in 2026.

Behaviour Driven Development is an agile approach to delivering software with the goal of the developers, testers and product owners or business analysts collaborate to have a shared understanding of intended behaviour through examples. These examples can then be formulated into test scenarios and automated to provide evidence that the desired behaviours are implemented and working successfully. These automated test scenarios are typically written in a human readable format known as Gherkin. The three phases of BDD are Discovery, Formulation and Automation. Note that tests written in Gherkin are not inherently BDD test cases as this requires completion the Discovery and Formulation phases.

Specification by Example is an agile approach to delivering software where the requirements are defined as executable specifications. Teams identify the scope of the work and illustrate the intended behaviour through examples. The key examples are refined into executable specifications which are then turned into automated tests. These test can then act as living documentation for the software. In order to provide human readable tests for the living documentation, tests may be written in Gherkin based frameworks or other frameworks such as Concordion or FitNesse. The methodology has significant overlap with BDD and ATDD.